A New Life for Lifeboats

Lifeboats are amazing. They and their volunteer crews save lives. They are designed and built to be tough – it’s a tough life – but they are well cared for and loved throughout that life. Eventually better lifeboats are designed and desired so the previous ones end their working life. For the materials they are made from, that’s just the end of life 1. What future lives could we give those materials?

“Our orange lifeboats need a green afterlife”

Recently I went to a fantastic event at the RNLI HQ, on Poole Quay. They have worked with LoToNo to bring together a wide group of people to innovate around this problem. They have 86 lifeboats that will be decommissioned over the next few years and as the market for resale is shrinking (and they are aiming for zero waste to landfill by 2024) they want to develop new ideas to keep these fine boats out of landfill.

Lifeboats into landfill “would break the crew’s hearts”.

RNLI Mersey Class All Weather Lifeboat

There is a lot of stuff here: 43 tonnes of electronics, 954 tonnes of composites, 43 tonnes of plastic & 412 tonnes of metal. So the RNLI have set up a “decommissioning challenge” and this technical briefing gave us all a chance to meet up and get hands on, on board. The weather was beautiful, the hospitality was great and everyone was enthusiastic. Let’s check out the boats:

There are 3 classes of boat that will be retired and we got a tour of the RNLB Bingo Lifeline. She’s a Mersey class boat, the smallest but most adaptable of the 3, which will be the first to be decommissioned. 11.6m long, 14 tonnes and built from 1988 to 1993, they can be launched from a trailer or a boathouse.

Interestingly the first 10 built had aluminium hulls but later versions were made in the ‘new-fangled composite’ GRP. From strong & recyclable to stronger & not very recyclable at all. As an all-weather lifeboat the Mersey is inherently self-righting if it capsizes (all the mass is very low down) when all the hatches are sealed. Big chunky hatches. It’s like going to sea in a tank.

Do what it says

Overengineering + meticulous maintenance = ideal for reuse?

That’s a lot of bolts

These boats are tough, purely functional and put together with more fasteners than I’ve ever seen. Are 30 bolts sufficient? Yes. So let’s use 80, just to be sure. This adds some cost and assembly time but it means you have a high level of redundancy in the parts. Plus every defect is carefully logged, meaning we have information on how the parts were treated. This is not common but from a Circular Economy perspective, it is ideal.

“These materials are good for crashing through waves, but not so good for recycling!”

Stella Job from Composites UK talked about the current recycling of composites – basically, it isn’t done a lot. There are only 2 sites in the UK that can process GRP. One plant can recover some fibres to be reused as reinforcement; the other mixes ground GRP and other materials to form a polymer concrete. The high embodied energy of composites can be recovered in part by burning off the resin, but this tends to damage the fibres so they become brittle and hard to recover.

Composites are “Intractable by design”

Intractable is an adjective describing high complexity, which makes it difficult to change, manipulate, or resolve an issue <Wikipedia>

What I found most interesting was that even after a hard life at sea, this GRP material will still retain most of its initial strength. As a polymer it was protected from UV degradation by paint, so in theory it can remain functional for decades, even centuries, to come. Shouldn’t we take advantage of this?

Of course in a marine environment non-metallic composites are fantastic at resisting corrosion, which can give them a 2-3 fold greater lifetime than steel or aluminium. Across the boat industry, GRP boats have been made for decades now and Carbon Fibre will no doubt replace GRP. That’s a lot of composite floating about, and nobody seems to know what to do with it. Various schemes have looked at this across Europe. The most in-depth seems to be BOATCYCLE.

Innovation

What came as a surprise was the focus the RNLI have on prevention instead of cure. Though they have big tough orange boats, they would prefer not to send one out in the first place. So one of their aims is to drastically reduce deaths in the ‘drowning chain’ which can be better achieved through education on, for example, best use of lifejackets. On a busy fishing boat a bulky lifejacket can get in the way during the day; they helped redesign them to be more discrete, so it’s more likely you’d wear it. Lifejacket design has come a long way:

So the RNLI have a desire to innovate but also a proud history and tradition. We were told this can cause conflict. It also means reputation is extremely important to them which adds another constraint in where these parts end up going. Gun boats or people smuggling on the news in a bright orange lifeboat is not desirable for the RNLI. Another interesting aspect to consider.

RNLI Shannon Class All Weather Lifeboat

The RNLI is now bringing boat-building in-house. They aim to turn out a new Shannon class boat (above) every 6 weeks. So the RNLI want to learn from this exercise to feed back into the design process for new generations of boat. This is just what needs to happen.

It struck me that as a charity with a long history, an ongoing purpose and an ability to design, build and maintain their equipment over decades, the RNLI is in a pretty unique position in terms of the Circular Economy. They are also world leaders in their field, both technically and with the training they offer, so it’s hoped that what is learned here could be feed out to the boat industry world wide. Exciting stuff.

Ideas

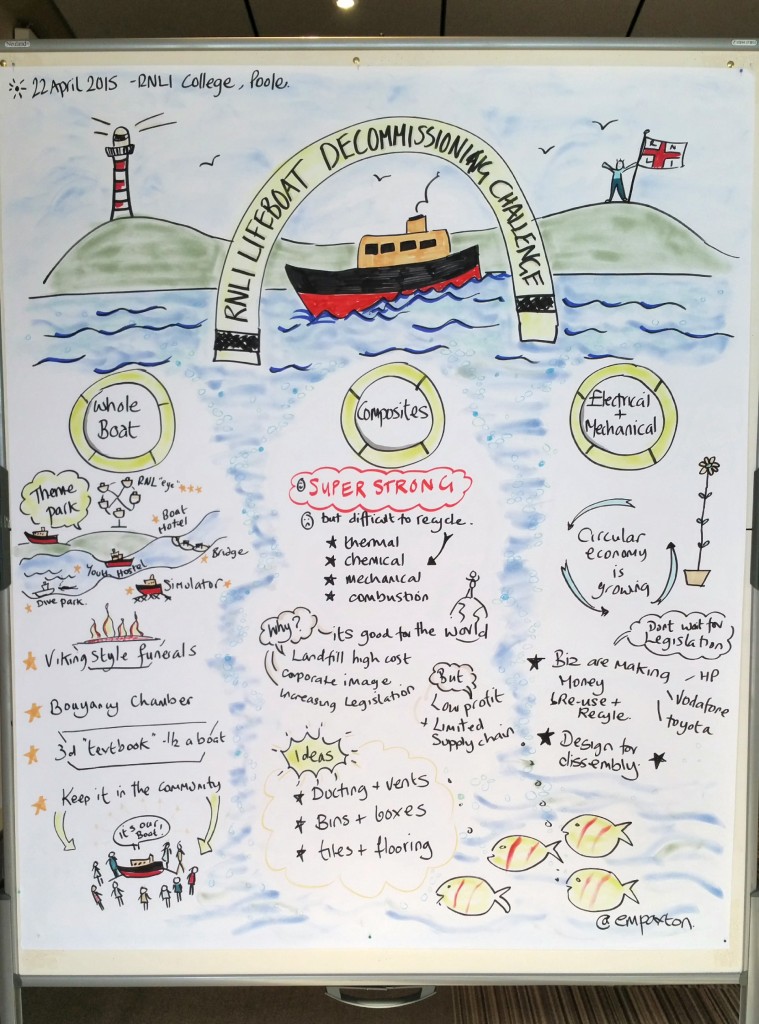

So what to do? We looked at the issue through 3 categories: Whole Boat, Composites and Electrical & Mechanical. We had some brainstorm sessions on Whole Boat with each table suggesting one idea, brilliantly captured above by Emma Paxton.

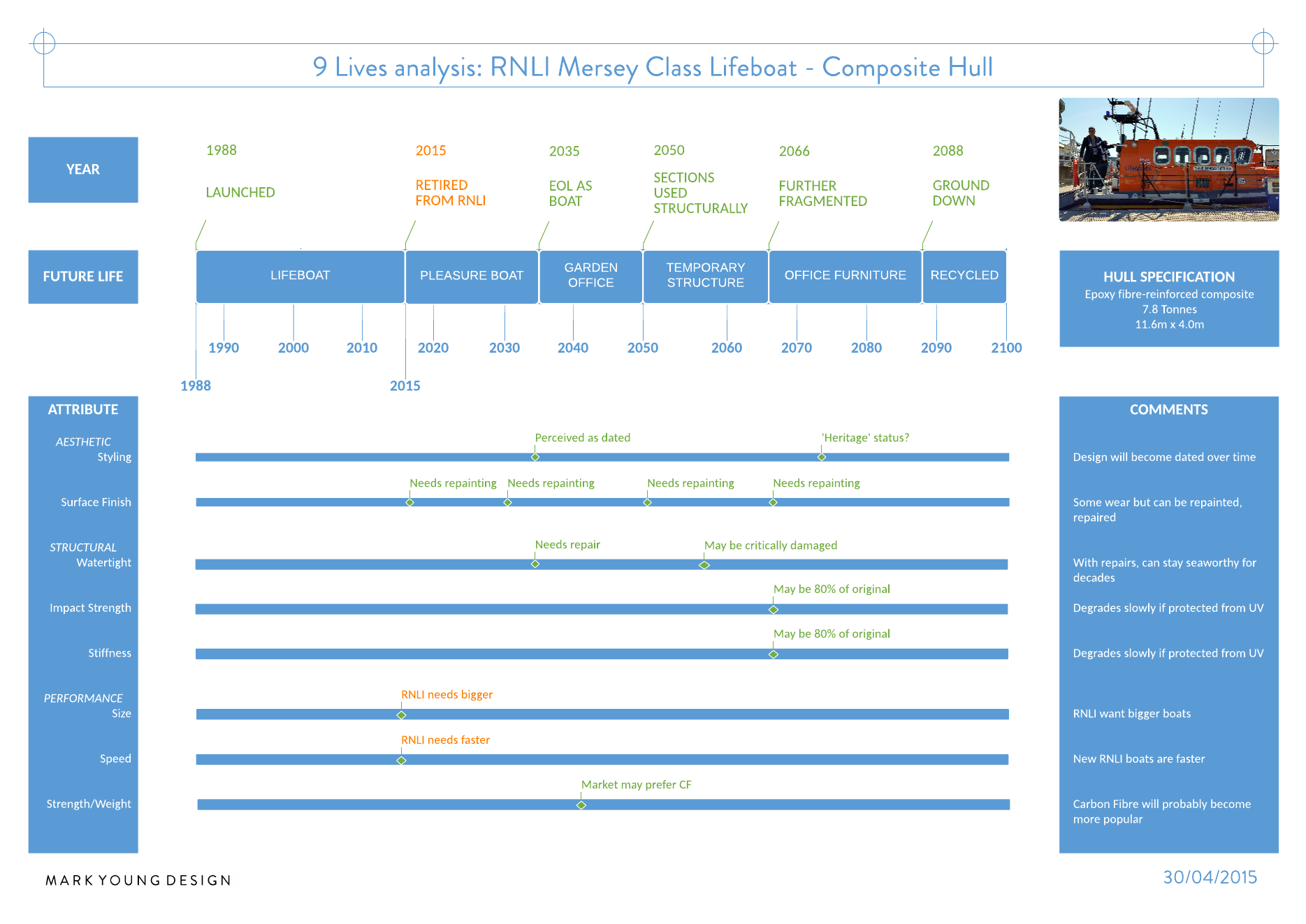

I’m particularly interested in the what to do with the Composite parts. So I’ve made a start on using my 9 Lives approach to analyse how the hulls may degrade and what might be the best way to use the material in decades to come before we think about shredding and recycling.